Food Systems

Over the millennia, our approach to securing food has evolved significantly—from a hunter-gatherer existence to the cultivation of crops through agriculture, culminating in today’s industrialized food system. This system emerged following the Industrial Revolution, which occurred approximately between 1760 and 1840, paving the way for the Green Revolution5. The latter revolution sought to make food more affordable, albeit at the expense of overlooking the environmental and social costs associated with food production. This led to a paradoxical scenario where overconsumption, food waste, and hunger coexist due to an unequal distribution of food access. The Green Revolution also heralded significant changes in our dietary habits, normalizing practices such as factory farming, the use of hazardous chemicals, the introduction of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), globalizing food supply chains, and contributing to the depletion of natural fisheries—all of which have had a profound impact on climate change4.

In Carbon County, Pennsylvania, this global narrative translates into a local crisis. The county, characterized by its rural landscape, grapples with low income and limited access to supermarkets across several communities, epitomizing the definition of a food desert1. In these areas, residents find themselves bereft of easy access to fresh fruits and vegetables. According to the USDA Economic Research Service Atlas, supermarket accessibility is notably poor, with urban areas lacking such amenities within a half-mile to a mile, and rural areas requiring a 10-20 mile journey, necessitating vehicle ownership, a significant barrier for low-income households1. While supermarkets and grocery stores in Carbon County are predominantly situated along major thoroughfares near residential zones, urban centers are dotted with gas stations and convenience stores instead. Despite the evident need, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services’ interactive map reveals a glaring absence of food banks within the county, further exacerbating the challenges faced by its residents in securing nutritious food2.

Agriculture

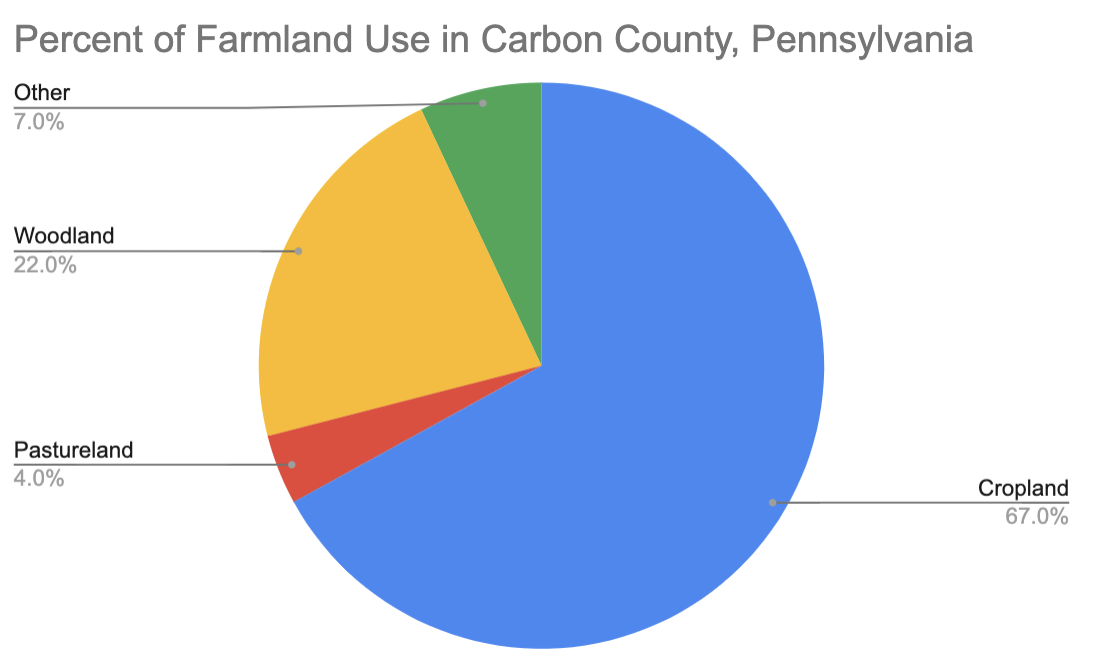

By 2017, the agricultural landscape of Carbon County had seen a notable shift, with farm land usage decreasing by 8% from 2012, as detailed in the Census of Agriculture County Profile3. This reduction left the county with 19,498 acres of land dedicated to farming, dispersed among 200 farms. Remarkably, 97% of these farms were family-operated, and a small but significant 1% committed to organic farming practices3. The primary crops cultivated across this acreage were forage hay, Christmas trees, corn for grain, nursery crops, and soybeans, with the land allocated to these crops varying between 600 and 3,800 acres3.

A critical issue with the agricultural model in Carbon County lies in its allocation of vast tracts of land to crops that fall short of supplying essential nutrients to the local population. Forage crops, destined for livestock feed, frequently rely on chemical fertilizers, mono-cropping, and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), all of which pose risks to local habitats and biodiversity. Additionally, corn and soybeans, staples of mono-cropping, exacerbate the strain on ecosystems through the use of industrial farming techniques. These include mechanized equipment that consumes fossil fuels and practices that lead to soil degradation4. The journey these crops take from field to livestock and processing facilities often spans considerable distances, further magnifying their environmental footprint.

The repercussions of such industrialized farming practices are far-reaching, including air and water pollution, soil erosion, and contributions to climate change, thereby affecting the county’s environment and its residents. The stakeholders entangled in these challenges range from local community members, who bear the brunt of environmental degradation and compromised food quality, to government agencies tasked with regulating farming practices and food production. Additionally, businesses involved in the farm-to-table supply chain and their investors are crucial players, as their decisions and practices directly impact the sustainability of agriculture in Carbon County and beyond.

Solutions

Fortunately, a variety of strategies exist to address the challenges of agriculture and food access within Carbon County, offering hopeful avenues for sustainable development. Embracing local produce and products stands out as a key measure against the pitfalls of industrial agriculture. The Lehighton Downtown Farmers Market serves as a vital source of local produce during the spring and summer months. Meanwhile, the Hometown Farmers Market and the Slatington Farmers Market, though located in adjacent counties and operational year-round, present accessibility challenges for some residents of Carbon County. Shopping at these markets not only bolsters local businesses and the economy but also faces constraints in terms of reach and availability.

Another innovative approach is indoor hydroponic gardening, which has seen significant adoption within the county. Little Leaf Farms, known for being Pennsylvania’s largest indoor leafy greens operation, utilizes hydroponics to grow lettuces in Carbon County, providing an appealing alternative to produce that has either been treated with pesticides or transported over long distances10. This technique is mirrored in Luzerne County, where Green Spirit Farms has transformed an abandoned warehouse for similar purposes, showcasing the potential for urban agriculture and sustainable practices9.

Beyond these, permaculture and polyculture present transformative alternatives to conventional farming by emulating the diversity and resilience of natural ecosystems. These methods promote a wide variety of crops, including perennial and compatible annual plants, to enhance soil vitality and improve the efficiency of water and nutrient uptake by plant roots. Incorporating native trees, grasses, and flowers around agricultural lands serves to mitigate nutrient runoff and curb water pollution, while simultaneously providing habitats for local wildlife and supporting biodiversity.

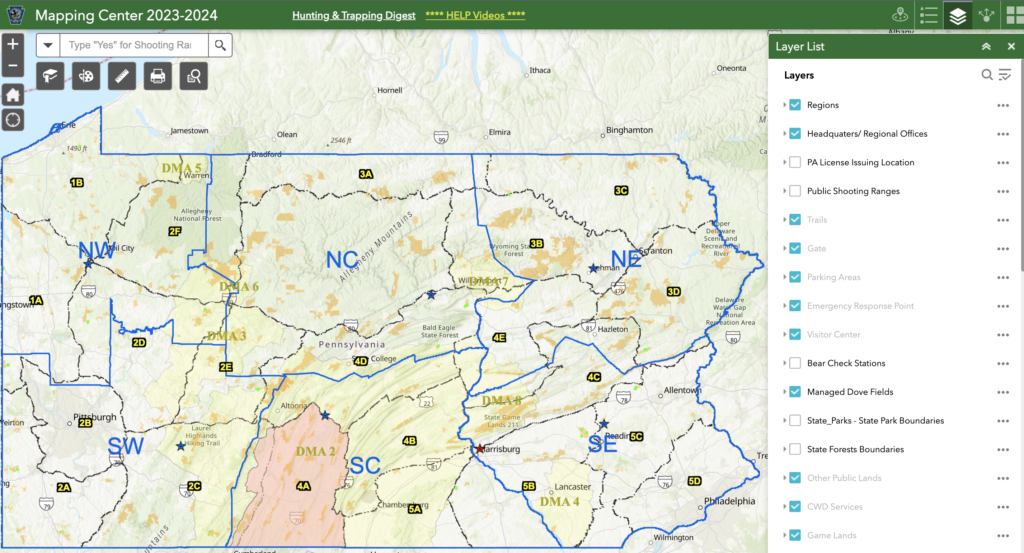

Preserving natural resources is another cornerstone for combating agricultural pollution and the broader impacts of climate change. With over two-thirds of its land designated as state game lands and state parks, Carbon County is a bastion of conservation, managed by the Department of Conservation & Natural Resources (DCNR)7. These areas are earmarked for recreational activities like hunting, hiking, and biking, offering sustainable alternatives to conventional meat consumption through regulated hunting. This practice leverages local ecosystems for food sources in a manner that is both natural and supportive of wildlife population management. Together, these solutions offer a multifaceted approach to enhancing food security, promoting environmental sustainability, and fostering a resilient local economy in Carbon County.

Limitations and Barriers

While promising solutions exist to mitigate the issues plaguing agricultural food systems and combat climate change, their implementation often encounters significant obstacles. Central among these challenges is the allocation of subsidies and funding. Financial support frequently favors producers of livestock feed and biofuels over those farmers dedicated to alternative and more sustainable practices. This misallocation underscores a broader systemic issue where incentives do not align with environmental sustainability goals.

Land conservation efforts also face uphill battles, with lobbyists pushing for the expansion of farmland and the growth of food processing industries at the expense of preserving natural landscapes. Such pressures complicate efforts to safeguard ecosystems and maintain the balance between agricultural development and environmental conservation. Despite these hurdles, permaculture and polyculture stand out as beacon solutions, aiming to restore the vitality of natural systems while contributing to ethical economic development and enhancing human well-being through improved food quality and accessibility. These practices embody a holistic approach to agriculture that, if widely adopted, could significantly impact sustainability and food security.

Conservation of natural resources presents another viable path toward sustainability, emphasizing the responsible extraction and renewal of resources to preserve biodiversity. The success of these efforts can be further amplified by initiatives from organizations like the Department of Conservation & Natural Resources (DCNR) that prioritize equitable opportunities and social justice, thereby ensuring that conservation efforts benefit all segments of society.

The path forward for small and sustainable farms involves concerted action, advocacy, and informed voting that reflects the community’s needs and priorities. In Carbon County, Pennsylvania, the potential for a vibrant, sustainable agricultural sector is evidenced by the presence of small farms like Senaka Farms and community hubs like the Downtown Lehighton Farmers Market, set to open in May. These local assets, along with others documented on sustainability asset maps, highlight the county’s rich resources and the potential for a more sustainable future.

Addressing the barriers to implementing sustainable agricultural practices requires a multi-faceted approach, including policy reform, community engagement, and a shift in societal values towards supporting local, environmentally friendly farming. Through collective effort and a commitment to sustainable principles, it is possible to overcome these challenges and move towards a more resilient and equitable food system.

Bibliography

1“Go to the Atlas.” USDA ERS, 2023, www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas/

2“Food Pantries.” PA Department of Human Services, n.d., www.dhs.pa.gov/about/Ending-Hunger/Pages/Food-Pantries.aspx. Accessed 28 Mar. 2024..

3“Carbon County Pennsylvania.” USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, n.d., www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Online_Resources/County_Profiles/Pennsylvania/cp42025.pdf. Accessed 28 Mar. 2024.

4Niesenbaum, Richard A. Sustainable Solutions: Problem Solving for Current and Future Generations. Oxford University Press, 2020

5“The Industrial Revolution.” National Geographic Education, n.d., education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/resource-library-industrial-revolution/. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

6“Sustainable Practices on DCNR Lands.” PA DCNR, n.d., www.dcnr.pa.gov/Conservation/SustainablePractices/pages/default.aspx. Accessed 28 Mar. 2024.

7Tonnelli, Nicholas. 2022. “Hunting Information.” The Nature Conservancy. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/pennsylvania/stories-in-pennsylvania/pennsylvania-hunting-information/.

8Vertical Farming Taking Root in Pennsylvania.” Public News Service, n.d., www.publicnewsservice.org/2014-07-24/rural-farming/vertical-farming-taking-root-in-pennsylvania/a40740-1. Accessed 8 Apr. 2024.

9Gruber, Philip. 2023. “Gov. Shapiro Celebrates Planned Opening of Pennsylvania’s Largest Indoor Leafy Greens Farm.” Lancaster Farming. https://www.lancasterfarming.com/farming-news/produce/gov-shapiro-celebrates-planned-opening-of-pennsylvanias-largest-indoor-leafy-greens-farm/article_3400e6f2-ffd0-11ed-8abf-536b1b59d9e5.html.

102017. Flickr growingwildfarm. https://www.flickr.com/photos/growingwildfarm/4483535954/.